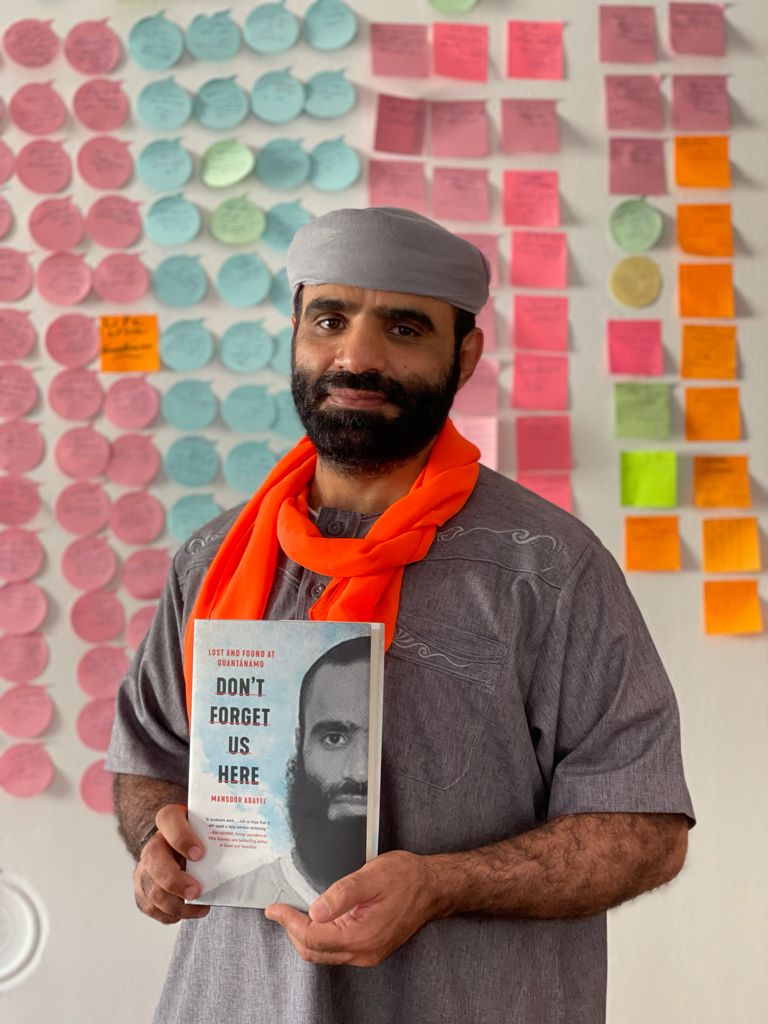

Photo Credit: Salwan Georges

We recently had the pleasure of sitting down virtually with Mansoor Adayfi, the author of Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. Mansoor is an activist and former Guantánamo detainee now residing in Serbia. At the age of only eighteen, he was kidnapped in Afghanistan and sold to the U.S. government. Held in Guantánamo for fourteen years, he was tortured and deprived of his basic human rights.

We talked with Mansoor about what he would go back and tell his younger self, his life in Serbia, and his recent college graduation. Now the Guantánamo Project Manager at the NGO CAGE, Mansoor and fellow former detainees, or “brothers,” have published an eight-point plan to instruct President Biden on how to properly close Guantánamo. Wearing a bright orange cloth around his neck out of solidarity for his brothers, Mansoor explained his plans to advocate for the closure of Guantánamo until they were free. As he spoke with conviction and humor, calling silence “a tool of the oppressors,” it became increasingly clear: Mansoor’s voice will be a powerful instrument of justice for years to come.

I would say to myself, stay strong, my friend. I am here with you.

At that time [when I was detained in Guantánamo], I was like, try to stay who you are, don’t lose yourself to the situation because at an early age, you are not experienced with life and you are dealing with people who are sophisticated, smart. They knew what they were doing and you just reacted. So sometimes I felt I let myself go in the reaction. You know, it’s just normal when you live under this cycle of violence, systematic torture, systematic abuse and so on. You go into cycles of hate, fear, anger, and loss.

I mean, I did my best…grew up and became a leader, organizing people, hunger strikes and so on. But you know, it’s not about blaming because there is nothing you can do about it. What I would tell myself to focus more on, you know, don’t let the situation change you because it changes people when you live in prison. Everything around you is designed as a jail where you start constructing a new way of life, you also will influence your character.

So I would say to myself, stay strong, my friend. I’m here with you.

What’s going on in Guantánamo is a symbol of torture, injustice, lawlessness, abuse of power. Indefinite detention.

Guantánamo is an idea. What’s going on in Guantánamo is a symbol of torture, injustice, lawlessness, abuse of power. Indefinite detention. Even a death sentence for the people there at Guantánamo now is one of the one of the biggest human rights violations in the 21st century.

Guantánamo wasn’t the worst place on the planet. Of course not, but it was the place that was established and designed to create the worst places on the planet in other places like China and Egypt, the Middle East and Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. Many countries have their own Guantánamo. Even France. A few months ago officials were calling to replicate Guantánamo, just without torture.

Guantánamo gives some people a kind of legitimacy to do the same. And why not? If someone likes it, if our boss can do it, why not? You know, those tyrants? They have no humanity. They have no remorse. They have no ethics. They have nothing that can stop greed, power and more power. I came from an Arabic background. I know my people very well like those tyrants. If you are not loyal, if you are not kissing their feet, they will kill you. We’ve got many gangs in Yemen who work for the Saudi authorities or for Emirates royalty. So if Americans can do that, Guantánamo can kidnap people, torture people, abuse people indefinitely, they can do that.

So, yeah, when the Bush administration chose Guantánamo, it was carefully chosen. They selected it to be like a temporary place to hold the worst of the worst of the terrorists, the professional killers. And also they didn’t want to give those people any rights. So. What’s going on? Guantánamo is a black site within a military base. In that place, you know, domestic or American law doesn’t apply, international law doesn’t apply. The Geneva Convention doesn’t apply. When we tip the balance of the system it becomes a tool of destruction.

They call them collateral damage.

America after 9/11, you know, the Bush administration misused and abused it. So what did they do? First of all, they constructed the language. War on Muslims, they call it the War on Terror. Kidnapping, they call it rendition. Prisoners of war, they call them detainees. Assassinations and the killing of millions, they call them collateral damage. And torture, enhanced interrogation techniques, prison detention. They created those realities, then they constructed a law to serve those realities. Americans, they have a law, they have a justice system. That system was created, you know, for the betterment of all Americans, for freedom, for rights and justice, to serve humanity. But when individuals start to utilize the system to serve some kind of agenda, chaos happens. They invaded Iraq, they invaded Afghanistan. Drone assassination. It ended up like around over one million killed and thousands of people imprisoned and tortured, over 30 million people displaced and entire families wiped out.

9/11 was used and abused for military expansion, you know, in various countries. And to achieve some kind of political and economic agenda in Afghanistan, in Asia and elsewhere. The American government at that time, you know, was like, ‘we are going to go as far as we want. We are not bound by any kind of law or anything. And nobody can do anything about it.’

That system that we created to protect us, to serve us, to help us, to achieve justice and peace, it becomes a tool of destruction, a tool of dehumanization. It becomes a tool of terrorism and fear.

They brought people from around the world. You know, the people of Afghanistan, they weren’t on the battlefield holding guns or carrying explosives. So they brought people from different parts of Afghanistan, from Pakistan, from Iran, from Saudi Arabia, from the United Arab Emirates, from Egypt, from Jordan, from Yemen, from Africa. Over 20 languages spoken by around 800 men. And what’s unique about Guantánamo? It wasn’t about safety or security or to make Americans safe.

No, the government played a role. They wanted to send the message to America, to the world, that there [in Guantánamo] are the worst of the worst. Because if you are going to learn to launch one of the biggest military campaigns in American history, you need to give people something to chew.

Guantánamo also turned out to be a laboratory. Guantánamo turned out to be a place where they developed enhanced interrogation techniques. Enhanced interrogation techniques studies were conducted, with psychologists, experts, advisors, and so on. And not just Americans. There were many countries that came to Guantánamo. They sent their own delegation to interrogate us. And China, they sent their interrogators to interrogate the Uyghurs.

Basically, I had no choice when I told them I didn’t want to go to Serbia.

Welcome to crazy Guantánamo. I had no choice when I told them I didn’t want to go to Serbia. They paid around 30-50 million dollars for Serbia to take [me and another detainee]. And they picked me up. They tied me, shackled me, put on handcuffs, and they flew me to Serbia. And it has been a lot since I left for the last five years. You know, our cases were handed over to the security facility, the secret police, and they treat us like terrorists. I went on hunger strike a few times. I brought with me, of course, the way of life, my behavior, everything. It’s not going to change. There should be some kind of rehabilitation or reintegration program which doesn’t exist.

The State Department sent a special envoy, a woman – her name is Heather. She came to me, she told me and saw everything organized. You stay there. You’ll get an education. Your family will visit. You have your own place, your stipend until it’s OK. But I said, I don’t want to. Still, I want to go to another country. But when I came here, the Serbians told me, we have nothing for you. We have a contract to keep him for two years and then deported back to Yemen. What? And imagine we have to start [a new life]. We have to fight for stuff for the kitchen. You have to fight for winter clothing. When I came here, they refused to give me money to buy winter clothing. They told us the Americans said not to give you a lot of money.

And since then, as I told you, I started asking for what was promised by the State Department. My lawyer flew here five times and tried to make things better. In 2018, I was threatened to be deported. They told me, you have the choice to go to the Saudi camp, to the Saudi jail, or to the refugee camp, and you have two months to evacuate from the apartment. We are going to evacuate you. So imagine – there was no income or legal status. I wasn’t allowed to study in the faculty. I was expelled, then my lawyer had to come. I had to go on hunger strike for 48 days, I almost died. It has been a lot. Then when I started speaking to the media about my situation, I was arrested, interrogated for around maybe 10 to 12 hours. I was threatened by the Secret Service and anyone I got in contact with, a friend or anyone I drink coffee with, they get arrested. They were interrogated and they were told to stay away. Until today, I had no friends in Serbia.

It’s difficult, you know, when you live in uncertainty. I want to build my life. I want to get married to have a family. I want to finish my college education. But here, I found it.

At Guantánamo, I was fighting for my freedom, but here I’m fighting for my life.

They threatened me. I met one of the young guys at the mosque and we went to drink coffee together. I met him last week, and he said, Mansoor, I cannot go because his name is on the blacklist. And he was called for interrogation three times, and they asked him, what do you know about Mansoor from Al-Qaeda, imagine to that extent? And when they asked about me in the mosque, wherever I go, do you know Mansoor from Al-Qaeda? Look at the question, how insidious it is. People are afraid now.

So for the last five years, I have been documenting everything as you see behind me, whatever I have done, talking to my lawyer, my brothers around the world. We have like three WhatsApp groups and I help them translating and trying to fix their problems. And last month, I finished my college and my thesis was about rehabilitation and reintegration of former Guantánamo detainees into social life and the labor market. I sent my thesis to the United States government, to the State Department and made some recommendations, you know? What they should do for the previous releases and recommendations for the new releases from Guantánamo. We published the book and we are still developing the TV show. And I am working now on the new book Life After Guantánamo. I couldn’t get married. I found a woman that I really loved but I wasn’t allowed to travel. This is my life, I mean, we live in Guantánamo 2.0.

You know, when I did my thesis, I talked all about the categories of different situations for these brothers. You know, some of them managed to integrate into the society and become productive members, families, jobs, businesses, and so on. Some of them still have problems. Some of them live a miserable life. You know, some of them lost their lives and we all live in the stigma of Guantánamo. And one of the cases too, like the Uyghur brothers, who were released from Guantánamo to Albania for the last 15 years they were released 2005 and 2006 until then they didn’t have any status, they didn’t have any IDs or documents. They cannot travel. They cannot work. Basically, they live like ghosts in that place. So welcome to our life after Guantánamo. It is still a big mess.

We are asking for justice. We were indefinitely detained. We were unjustly detained in prison and tortured, abused and so on. They destroy our lives. At least, you know, we seek justice to our case. That is what we want. What does justice mean? Justice means acknowledgment. You know, apologizing and also compensation so people can live their lives. So they should tell those countries, get the fuck off and let the people live their lives. Because, you know, Americans, they threw us to the countries and the countries fuck our lives again. We live in countries who were actually hired, for example, Serbia and other countries, they were given millions and millions of dollars to do the dirty work for the Americans. They view us as terrorists. I used to go [to the mall] because I live in one room and [was] like inside for the last two years. So I have to go someplace to work and be social and see people. There was a library in the mall. I used to go to pray to the second floor to the balcony. Nobody could see me, only the camera. [But then] the security guards called the police.

They called and a SWAT team came. I was detained, interrogated. I was kicked off the building simply because of that. So sometimes we feel like it’s a crime being Muslim.

First, [Antonio Aiello and I] released the book Don’t Forget Us Here. That book was written at Guantánamo. Twice. The first time, 2010 until 2013, but it was confiscated. Then I wrote it again in 2015, when I got my new lawyer. I used to write it to her as I used to go to the classroom while I was chained to the floor, shackled. I wrote it as legal letters. Every week I would send a bunch of letters to the secure facility and she collected them and sent them to Guantánamo for a look through it. And I got lucky they authorized the book.

We managed to finish the book [Don’t Forget Us Here], and now I work on another book, Life After Guantánamo. Since I got out I started documenting my life, my problems, you know, because there is this gap in my life of 15 years and I am being released to a place where I have no family, no friends, no community, nothing. And there is a lot of change in this crazy world. There’s a huge gap in my life. I’m still learning about the world until today. But it’s not just my story, it’s a story about other brothers, a story about the world, about, you know, our life and so on. So it will be a unique book because it’s the only book that will cover life after Guantánamo so far.

So after Guantánamo, it’s my duty as a prisoner there just to stand and to fight for the brothers who are still there, for the human beings that are trapped behind those walls.

I have joined the NGO CAGE, which has the Guantánamo Project and I have joined as the Guantánamo Project Coordinator. [Myself and other former Guantánamo detainees] also have a plan to close Guantánamo. It is an eight point plan that we sent earlier this year to President Joe Biden on how to close Guantánamo.

We are working now, trying to help the Biden administration close the detention. We are suggesting they communicate with lawyers. My thesis was part of that project trying to help to close the detention with some recommendations and so on, because it’s our duty.

I’m also campaigning with with the other organization like Amnesty International, Witnesses Against Torture and many others. So it was writing and interviewing and doing a lot of interview work in that field, pushing for just the closure of Guantánamo. We find the idea of Guantánamo is not just about Guantánamo, and I hope in the future I can find a job in activism. We can start maybe by creating an organization to fight against indefinite detention and torture everywhere around the world. I don’t know if I knew the world before Guantánamo, to be honest with you. But it’s not what I imagined it to be. When I got out, I was shocked. Wars, killing, starvation, famine.

I started with activism at Guantánamo actually, before, not after Guantánamo. Guantánamo was wrong. So like this is in a sense, why should we follow it? We should do something about it so we started a hunger strike. We start by resisting. We start protesting. We boycott the interrogation, boycott the ICRC. We try to use the most peaceful method we could, sometimes by hurting ourselves with the hunger strike. But even that action was presented to be like an act of terrorism. Or they accused us of being Al-Qaeda, a terrorist cell at Guantánamo.

And after Guantánamo, you know, as a man who lived in Guantánamo, who knew a lot about Guantánamo, who was a victim of Guantánamo. I met many people like me who are still there. And if I learned something, you know, as human beings, there should be rights as a human regardless of what you did. If you are a criminal, if you are a terrorist, there should be basic rights for everyone. You cannot just kidnap someone and torture him and abuse him and say he’s a terrorist. Without any kind of proof.

If we believe in a justice system that should be applied to everyone. I’m not trying to give any criminals or terrorists some kind of rights, but it’s about us as a human, as humanity, it’s about us all. So what happened to us? Rights don’t exist, justice doesn’t exist. And I don’t think it will ever exist unless something changes in the United States. So we were fighting for justice, for the basic right to be treated as a human being and to challenge our imprisonment and so on. But you are a place, we were in a place that is outside of the law, outside any kind of jurisdiction. So of course, trying to survive is also activism because we saw many brothers who gave up many people who died at Guantánamo, people who totally became crazy. We see people with broken backs, no teeth and eyes. And so someone has to do something about that. So after Guantánamo, it’s my duty as a prisoner there just to stand and to fight for the brothers who are still there, for the human beings that are trapped behind those walls.

If someone is a criminal or someone has committed a crime, we believe in justice. They should be tried. They should be put in the justice system and tried. It’s simple.

I know the pain of injustice. I know the deprivation of rights. And I don’t want anyone to experience that feeling or to be in that situation or with it in that way. So yes, I choose to do this activism, although, you know. I have been threatened many times, and it’s just going to create a lot of difficulties. Because some of the brothers who were released to other countries, they had to sign a document that they will never talk to the media. Fortunately, I was dragged to Serbia against my own will. I never signed anything, I will never sign anything. And they told me they’re going to make my life hell if I don’t stop talking to the media. I said OK. I don’t give a shit about it because I have nothing wrong. I was accused to be to doing something like propaganda for terrorism. That’s what it is when I talk to you guys, doing interviews, publishing the book. They look at it like you are doing propaganda for terrorism.

Like, you know, keeping silent. It’s another form of oppression, but also gives power to the oppressors. And it’s also a tool for the oppressors, because if nobody talks about the injustices done, they’ll never stop. They will keep on and go on and go on.

I would like to invite the readers to call for the closure of Guantánamo and Guantánamos all around the world.

And to those tyrants, oppressors, we are on your back. That’s as individuals, but as humans, and we’re going to fight for justice for rights for all human beings regardless. That’s it. A simple message.

Get your copy of Mansoor’s Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found in Guantánamo here. To support Mansoor in his new life in Serbia, donate to his fundraiser here.