By Saul R. Revatta

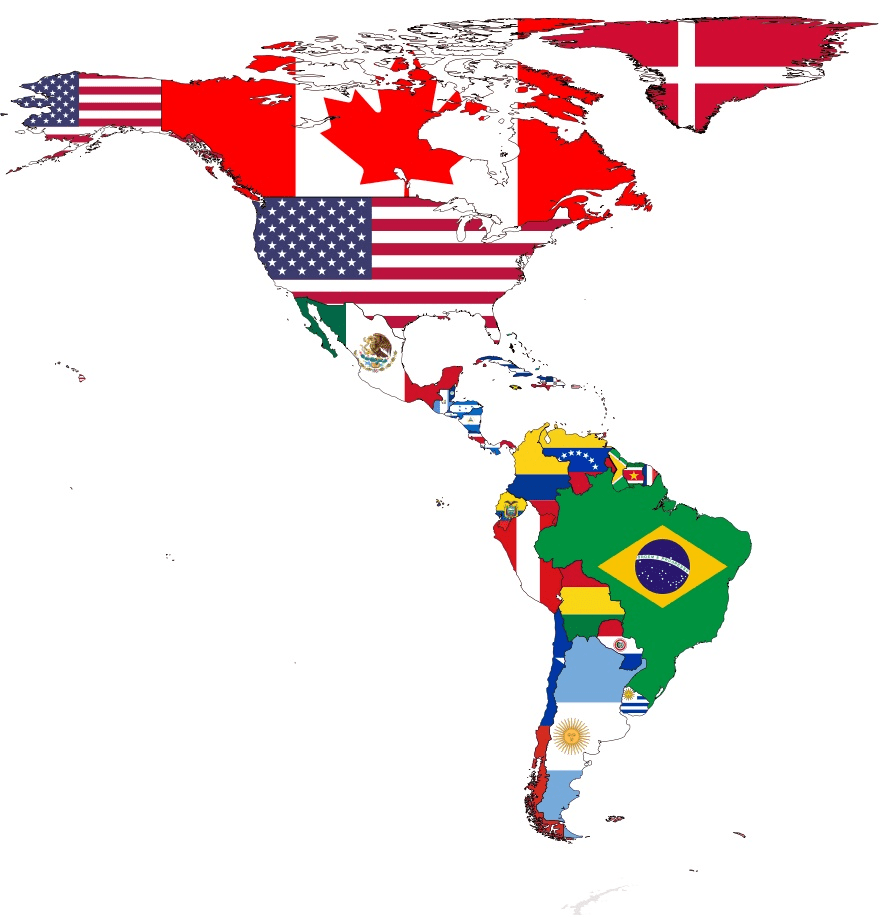

There is no doubt that since the end of World War II, the United States has been the dominant force shaping and leading the global economic order. The U.S. has spearheaded a Western-led rules-based capitalistic system that has fueled global economic growth but has also disproportionately benefited the U.S. and its western European allies. However, as of late, the U.S. has forgotten the tremendous economic gains it has reaped as the primary architect and enforcer of this system. Nowhere is this abdication of leadership more evident than in Latin America (LatAm), where the U.S. is ceding influence to China, which has been funding major infrastructure projects across the region. The incoming Trump administration must know that it is in the U.S.’s best interest to re-engage with LatAm and regain influence.

The history of U.S. involvement in LatAm is fraught with controversy. Washington has a history of supporting authoritarian regimes to curb leftist movements, from Pinochet in Chile to Castelo Branco in Brazil, which have infringed on the sovereignty of the region throughout the late 20th century.

Since the turn of the millennium, LatAm’s economies have grown from USD 2.2 Trillion in 2000 to USD 6.7 Trillion in 2024. Throughout this growth, Latin American nations have sought to diversify their economies and reduce their reliance on resource extraction. The U.S., as an economic leader, instead of fostering the region’s manufacturing and industrial base closer to home, has primarily overlooked these opportunities, leaving a void in investment in an area that is home to a young and increasingly educated population.

Looking at this foreign investment void, Beijing has stepped in, promising investment and development while assuring LatAm leaders that it will treat them as equals, not as less significant leaders, which is how many LatAm leaders feel perceived by U.S. politicians. Moreover, China’s stance of non-interference in domestic politics has been appealing to central and local governments in the region, many of which have been stained by corruption scandals and self-dealing.

LatAm is full of politicians who are eager to show that they can attract foreign investment; yet, despite China’s promises of equal partnership and economic development, the results have been lackluster. Many Chinese-led infrastructure projects have fallen short of expectations as is with the Coca Codo Sinclair Hydroelectric Plant in Ecuador which has faced constant technical and structural issues, or the Mar 2 Highway project in Colombia which has been criticized by mainly employing Chinese workers. While investments in copper extraction in Peru and Ecuador serve primarily to feed China’s industrial appetite, these reinforce the commodity-based economic model that the region must escape for its long-term prosperity.

The new port of Chancay in Peru, alongside China’s export-driven economy, demonstrates the Chinese government’s probable aversion to developing LatAm’s industrial base.

The U.S. must not forget that a primary reason for its privileged low interest rates, even when running high deficits, is that the U.S. dollar is still the primary currency of exchange among countries including LatAm. Forgoing investment in the region will make the area more dependent on Chinese influence and more willing for countries to increase their Yuan reserves and decrease their U.S. Dollar reserves to use in their regional trade and their increasing trade with China.

The key for the U.S. to maintain and strengthen its influence is not by promoting more resource extraction in LatAm, but by investing in genuine economic development projects that foster sustainable growth and technological innovation. Local companies alone cannot provide the necessary financing for the projects needed as they lack the cheaper and vast capital that U.S. companies enjoy. By helping LatAm countries build industries of the future, the U.S. would not only strengthen its ties to the region but also secure a strategic, economically vibrant partner close to home.

Moreover, LatAm itself stands to benefit from a renewed U.S. partnership. The region’s long-term prosperity depends on whether it can transition from being a raw materials exporter to a more diversified, industrialized economy. While the responsibility for this transformation lies primarily with LatAm nations, meaningful support from the U.S. could make this uphill climb more manageable.

The U.S. government can seize the opportunity to demonstrate that it understands that improvements in the region are a net gain for the U.S., or lose its influence in the region to China, which has made promises to turbocharge the region without criticizing the region’s political disasters. The more the Chinese government invests in the region, the more they will have a say in the affairs there, which could include a military presence as an excuse to defend its investments. Ultimately, whichever nation presents the best value proposition for the region will have a significant and lasting influence in Latin America.