Inspired by her documentary and forthcoming book, The Banker Ladies, we recently had the privilege of connecting with Dr. Caroline Shenaz Hossein about her research on coop banking, the role of rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs), and social enterprises in Canada.

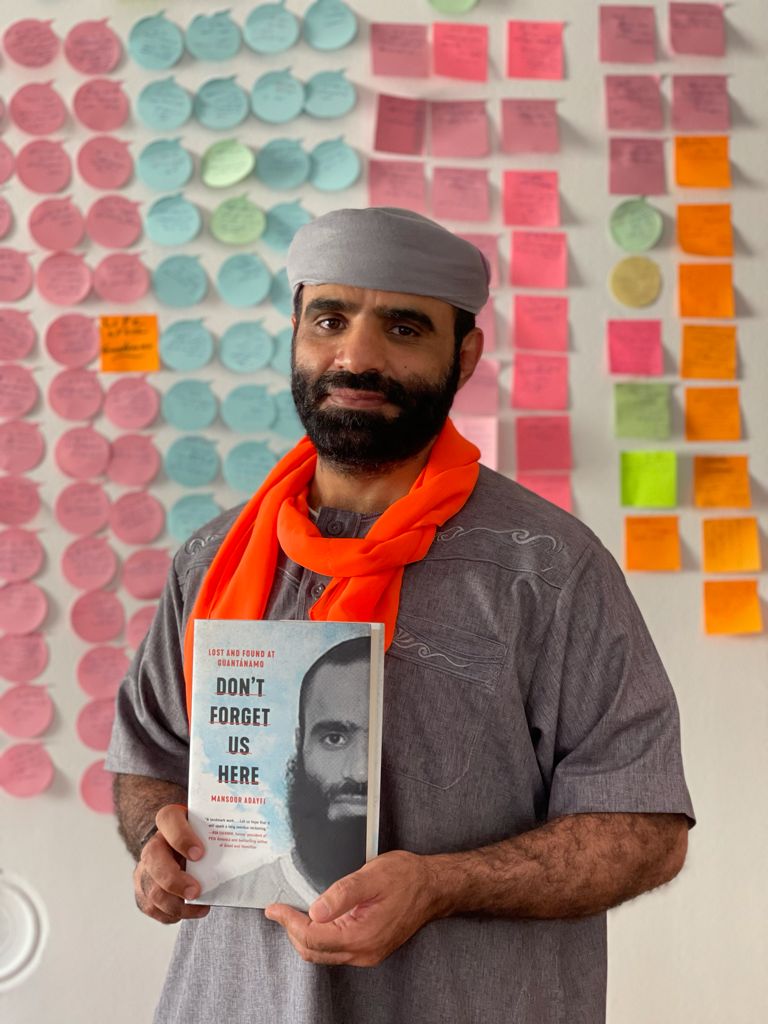

Caroline Shenaz Hossein is an Associate Professor of Global Development and Political Science at the University of Toronto at Scarborough in Ontario, Canada. She founded the Diverse Solidarity Economies (DiSE) Collective, made up of more than 20 Black and racialized feminist leaders, and is the author of Politicized Microfinance: Money, power and violence in the Black Americas (University of Toronto Press, 2016). Caroline currently sits on the Board of the International Feminist Economics Association, is the Board Chair of the Miami Institute for Social Sciences, and is a Board trustee of the Association of Social Economics, all global academic institutions reaching thousands of members. She is currently conducting research on the African diaspora in Canada and the Caribbean, and she is particularly interested in advancing the economic role of racialized women in the Caribbean and Canada in real ways to acknowledge and hire the Banker Ladies in economic development. You can see more about her research and projects on her website or follow her on Twitter: @carolinehossein.

- What has your career journey been like and what inspired you to create the Banker Ladies documentary and research alternative models of banking?

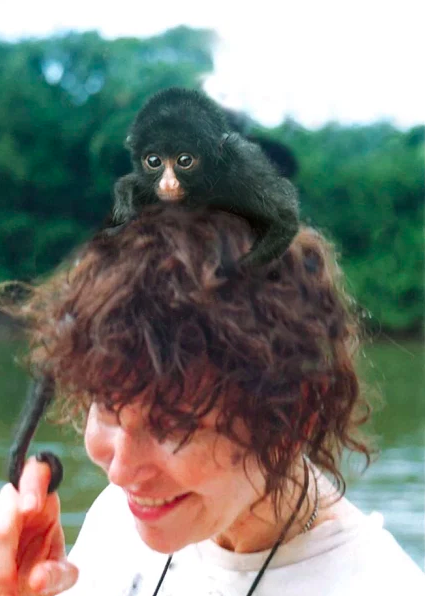

While at Cornell University (1995-1997), I started researching Sudanese exiles in Cairo, Egypt and livelihood strategies such as Sandooq and other microbanking programs. I then worked in Benin, Niger, Guinea, and a number of other places focused on economic development programming through global non-profits and development aid agencies for about 10 years. Now as an academic, I am interested in coops and the commoning of goods. Though I studied professionalized financial development, such as microfinance, for years as my PhD topic across a number of Caribbean countries, my interest was always in community-driven cooperative institutions, officially known as rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs). ROSCAs are locally called by the vernacular: Susu, Chit, Hagbad, Osusu, Chama, Arisan, Hua and such banking coops. Being told that there was only one commercial model of banking to follow seemed untrue. Growing up in a Caribbean immigrant family we had to struggle for everything, and I knew that right in Toronto African peoples and other racialized immigrants were always organizing their own mutual aid financing and coops, and often did this work out of sight. This is what we can see as part of the commons, in which people shared goods to help themselves and others. In my experience, doing research on ROSCAs is accepted in the academe, as long as one is studying these coops in the Global South, outside of the Western world. Running a ROSCA is tough work because the members who organize these coops are operating informally, and they are commoning resources so building trust takes time. Because I focus on Black marginalized women, this takes even more time to get the story right due to the secrecy at times with informal coop systems. I am working on my fifth book, The Banker Ladies, and the Canadian case is the hard one to do because the ROSCA members – known as the Banker Ladies – hide what they do. The documentary is directed by a Haitian-Canadian filmmaker Esery Mondesir and the goal is to bring awareness and to educate the public about ROSCAs, informal coops, and mutual aid carried out by marginalized Canadian women. The Banker Ladies is hosted on films for action (open access) and it was supported by federal SSHRC funding and the early researcher award by the Province of Ontario. This body of work on ROSCAs in the Americas is based on 11 years of research and I have a book, The Banker Ladies, underway with the University of Toronto Press.