Traducido por Pilar Espitia

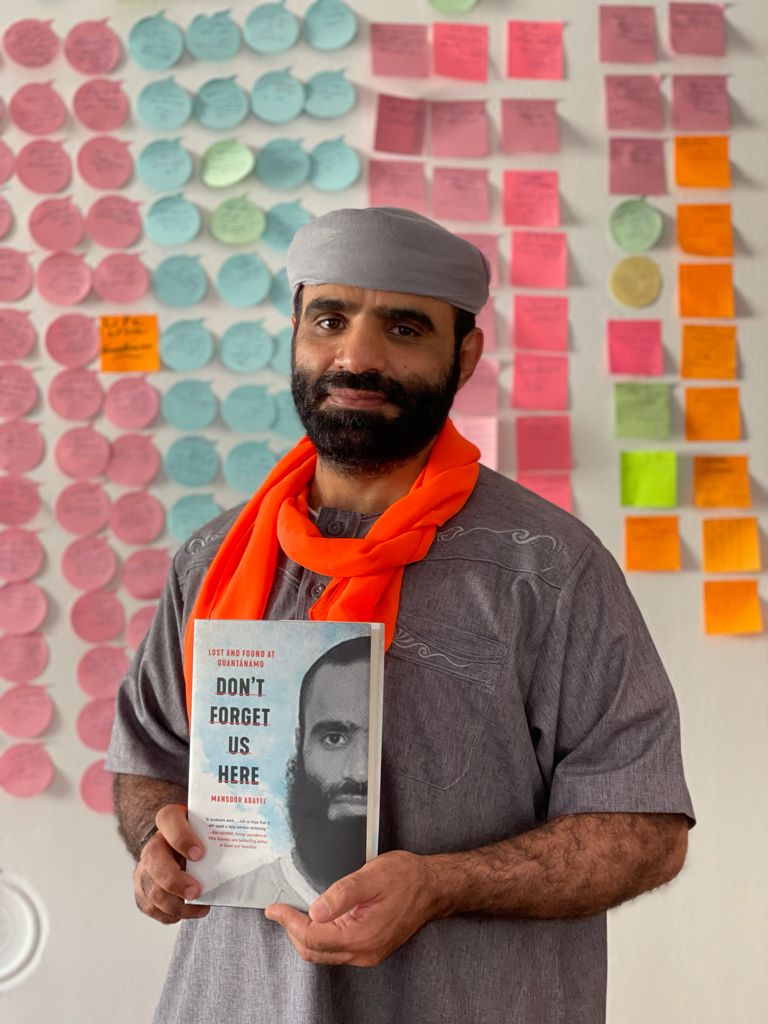

Hace poco tuvimos el placer de sentarnos a conversar virtualmente con Mansoor Adayfi, autor de “Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo” [“No se olviden de nosotros: De cómo me perdí y me encontré en Guantánamo”]. Mansoor es activista, ex-prisionero de Guantánamo y actualmente reside en Serbia. A la edad de tan solo dieciocho años, fue secuestrado en Afganistán y vendido al gobierno de los Estados Unidos. Retenido en Guantánamo por catorce años, fue torturado y despojado de sus derechos más básicos.

Hablamos con Mansoor sobre lo que le diría a la versión más joven de sí, si pudiera volver en el tiempo, sobre su vida en Serbia y su reciente graduación de la universidad. Como gestor de proyectos de la ONG llamada CAGE, Mansoor y sus antiguos compañeros de prisión, o sus “hermanos”, han publicado un plan de ocho puntos para instruir al Presidente Biden sobre cómo cerrar Guantánamo de forma apropiada. Alrededor del cuello, Mansoor portaba un pedazo de tela naranja para simbolizar su solidaridad con sus hermanos y explicó sus planes para defender el cierre de Guantánamo hasta que sus hermanos fueran libres. Mientras Mansoor hablaba con convicción y humor, llamando al silencio “la herramienta de los opresores”, poco a poco se volvió claro que su voz será un instrumento poderoso de la justicia en los años venideros.